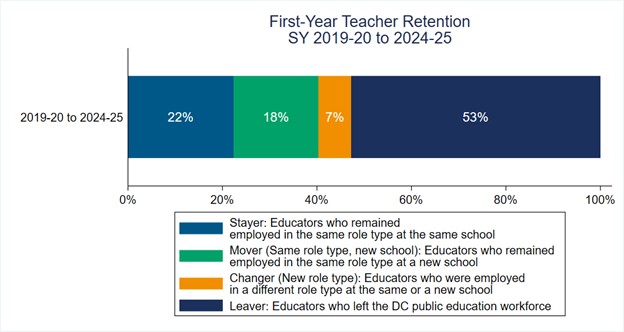

What percentage of first-year teachers in DC are still working in public schools in DC five years later? National longitudinal studies over the past three decades have estimated that 40-50 percent of first-year teachers leave the profession within five years (Ingersoll, Merrill, Stucky, & Collins, 2018; Ingersoll, 2003). While OSSE reports annually on the retention of DC’s public school educators, the agency has not previously examined or publicly shared the long-term retention of first-year teachers. Data from the annual Faculty and Staff data collection from the 2019-20 school year through 2024-25 show that 53 percent of first-year teachers in the District’s public schools in the 2019-20 school year were no longer working in a DC local education agency (LEA) in the 2024-25 school year (Figure 1). Twenty-two percent were still teaching in the same school where they started in 2019-20, 18 percent were teaching in a different school in DC, and 7 percent were working in a DC LEA, but not as a teacher.

Figure 1. First-year teacher retention SY 2019-20 to 2024-25

Notably, the years covered by this analysis contain the COVID-19 pandemic years, which were marked by a high degree of disruption for schools, including a year of almost entirely remote instruction in the 2020-21 school year. Nevertheless, these data illustrate that DC schools have experienced high rates of novice teacher attrition over the last five years. Because teachers improve most rapidly at the beginning of their careers, this so-called “revolving door” effect is potentially harmful to students who are frequently taught by early-career teachers rather than more experienced teachers (Ingersoll, 2004).

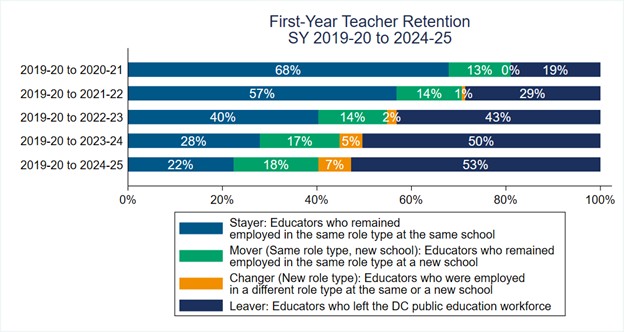

Figure 2 shows the year-by-year breakdown of 2019-20 school year first-year teacher retention over these five years.

Figure 2. Annual retention of 2019-20 first-year teachers over five years

This figure shows a steady decline over time in the number of first-year teachers in 2019-20 who remained as teachers in the school where they began teaching in2019-20. While 13 percent of teachers transferred to a new school after their first year of teaching, this percentage stayed relatively constant after the first year, with few additional teachers transferring to new schools from their second year of teaching onward. The number of first-year teachers in 2019-20 who moved into non-teaching roles within DC LEAs increased over time, perhaps reflecting internal promotions into administrative roles. Finally, the number of first-year teachers in 2019-20 who exited the DC public education workforce entirely increased steadily over the first three years of teaching, before tapering off in the fourth and fifth years.

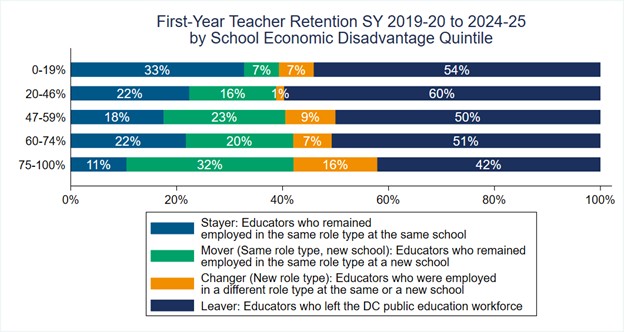

Literature also consistently shows that teacher retention tends to be lowest in schools serving the most economically disadvantaged students (Sutcher, Darling-Hammond, & Carver-Thomas, 2016; Carver-Thomas & Darling-Hammond, 2017). These trends hold true in DC as well; first-year teachers in the 2019-20 school year who taught in schools with higher proportions of economically disadvantaged students were significantly less likely to stay in their schools five years later than first-year teachers who taught in schools with lower levels of economic disadvantage (see Appendix for logistic regression results). For example, of 2019-20 first-year teachers in schools in the lowest poverty quintile, 33 percent continued teaching in the same school five years later, whereas only 11 percent of those who started teaching in the highest poverty quintile remained in the same school after five years.

A first-year teacher’s odds of moving to another school in DC had the opposite relationship with the school’s level of economic disadvantage; teachers in more economically disadvantaged schools were more likely to move to another school over the course of five years than teachers in less economically disadvantaged schools. For every 10-percentage-point increase in the percent of students who are economically disadvantaged in a school, a first-year teacher’s odds of moving to a different school within five years increased by 22 percent. Interestingly, a school’s level of economic disadvantage did not have a significant relationship with a first-year teacher’s odds of either changing to a non-teaching position or leaving the educator workforce altogether. Figure 3 shows the five-year retention of 2019-20 first-year teachers by their school’s quintile of economic disadvantage. In this figure, the first quintile represents schools that have the lowest rates of economic disadvantage, and the fifth quintile represents schools with the highest rates of economic disadvantage.

Figure 3. First-year teacher retention SY 2019-20 to 2024-25 by school economic disadvantage quintile

This figure illustrates that the percent of first-year teachers who stayed in the same school five years later tended to be higher in schools with low levels of economic disadvantage and lower in schools with high levels of economic disadvantage. These differences are almost entirely explained by the number of teachers moving between schools; the percentage of teachers who changed schools was low in schools with low levels of economic disadvantage and high in schools with high levels of economic disadvantage. The percent of first-year teachers who moved into non-teaching roles or left the educator workforce altogether was unrelated to their school’s level of economic disadvantage.

Importantly, research indicates that the disparities in teacher retention by school demographics are not necessarily caused by the student demographics; rather, the factor most consistently associated with teacher retention and turnover is administrative support (Sutcher, Darling-Hammond, & Carver-Thomas, 2016). However, teachers tend to find their administrators unsupportive more often in schools with high levels of economic disadvantage, leading to lower teacher retention rates in economically disadvantaged schools. These findings suggest that strong mentoring and induction programs, supportive working conditions, and principal training programs in DC could slow the churn of beginning teacher turnover, allowing students to benefit from stability in their schools and experience in their classrooms.

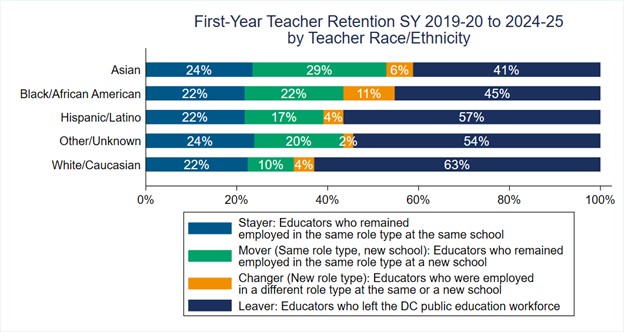

Research also shows that retention rates can differ by teacher’s race, with Black or African American teacher retention rates often lower than those of white teachers (Farinde, Allen, & Lewis, 2016). In DC, Black or African American and white teachers tend to be retained at similar rates from year to year. However, when examining first-year teacher attrition over a five-year time period, Black or African American and white teacher attrition rates look very different. White first-year teachers in the 2019-20 school year had nearly twice the odds of leaving the DC educator workforce within five years compared to Black or African American teachers, after controlling for school-level economic disadvantage (see Appendix).

Figure 4. First-year teacher retention SY 2019-20 to 2024-25 by teacher race/ethnicity

As the graph shows, the difference in the percent of white vs. Black or African American first-year teachers who left the workforce is not driven by higher retention of Black or African American teachers in their first school of employment. It is driven by higher numbers of Black or African American teachers moving schools or changing to non-teaching roles within the public school system rather than leaving the DC public education system entirely.

References

Boyd, Donald, Pam Grossman, Hamilton Lankford, Susanna Loeb, and James Wyckoff. 2008. Who leaves? Teacher attrition and student achievement. Washington, DC: National Bureau of Economic Research.

Carver-Thomas, Desiree and Linda Darling-Hammond. 2017. Teacher Turnover: Why it Matters and What We Can Do About it. Palo Alto, CA: Learning Policy Institute.

Farinde, Abiola A., Ayana Allen and Chance W. Lewis. 2016. “Retaining Black teachers: An examination of Black female teachers’ intentions to remain in K-12 classrooms.” Equity & Excellence in Education, 49(1): 115-127.

Gray, Lucinda, Soheyla Taie, and Isaiah O’Rear. 2015. Public school teacher attrition and mobility in the first five years: Results from the first through fifth waves of the 2007-08 beginning teacher longitudinal study. Washington, DC: National Center for Education Statistics.

Ingersoll, Richard, Elizabeth Merrill, Daniel Stuckey, and Gregory Collins. 2018. Seven Trends: The Transformation of the Teaching Force – Updated October 2018. CPRE Report. Philadelphia: Consortium for Policy Research in Education, University of Pennsylvania.

Ingersoll, Richard. 2003. Is there really a teacher shortage? Seattle, WA: Center for the Study of Teaching and Policy at University of Washington.

Ingersoll, Richard. 2004. Why do high-poverty schools have difficulty staffing their classrooms with qualified teachers? Washington, DC: Center for American Progress.

Sutcher, Leib, Linda Darling-Hammond, & Desiree Carver-Thomas. 2016. A coming crisis in teaching? Teacher supply, demand, and shortages in the U. S. Palo Alto, CA: Learning Policy Institute.

(Logical regression results are available in the appendix.)